State of Exception in its 7th month

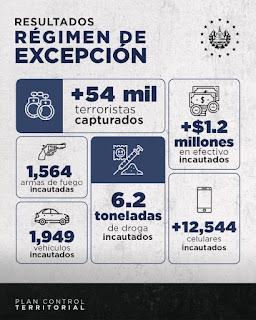

The Bukele regime proclaims that it has now arrested more than 54,000 persons alleged to have ties to the gangs since March 27. And daily it continues to announce additional arrests of persons that security forces say are tied to one of the country's street gangs.

Starting Saturday, October 1, police and military set up a cordon around the town of Comasagua, searching all who entered or left as security forces searched for gang members allegedly linked to a recent killing. By Monday, police said they had captured more than 50 linked to the Witmer Locos Salvatruchos cell of MS-13 in the area.

The government tweeted out videos like this one of the operation:

A poco más de 24 horas de iniciar el #CercoComasagua, la @PNCSV y la @FUERZARMADASV capturaron a Carlos Alberto Mancía Pérez alias “Chan Chan” y Carlos Antonio Valladares Corea alias “Delincuente”, terroristas responsables del asesinato cometido el sábado 1 de octubre. pic.twitter.com/N9NspdcvHv

— Casa Presidencial 🇸🇻 (@PresidenciaSV) October 3, 2022

Videos like this are designed to convince the public that the State of Exception needs to remain in place.

The significant reduction in homicides across the country continues. Even when you include the deaths of gang members in confrontations with police or the deaths in prison, which the government excludes from its public tally of homicides, the number is still historically low. Hence the Salvadoran public continues to express high levels of support for the State of Exception despite the numerous voices who are expressing concern over human rights violations.

|

| El Salvador government graphic on results of State of Exception |

Although Nayib Bukele has declared that El Salvador is now the safest country in Latin America, the Legislative Assembly continues to vote for monthly extensions of the State of Exception. The Legislative Assembly prolonged the State of Exception for a seventh month on September 14, with no indication this would be the last extension.

The popularity of the measure provides the political cover for the ongoing extensions rather than the existence of the emergency conditions required by the Salvadoran constitution. Article 29 of the Salvadoran Constitution establishes that rights can only be suspended "in cases of war, invasion of territory, rebellion, sedition, catastrophe, epidemic or other general calamity, or serious disturbances of public order." Even if one views the paroxysm of violence on the weekend of March 26-27 as a "serious disturbance of public order," the government's own celebrations of public safety six months later completely undercut the idea that extensions still have their original constitutional basis.

The cost to achieve the current results has been widespread instances of human rights violations. The human rights group Cristosal reports that it received 2775 complaints of arbitrary detentions during the first six months of the State of Exception. Within those detentions were 47 persons with disabilities and 223 persons with chronic medical conditions.

The cost to achieve the current results has been widespread instances of human rights violations. The human rights group Cristosal reports that it received 2775 complaints of arbitrary detentions during the first six months of the State of Exception. Within those detentions were 47 persons with disabilities and 223 persons with chronic medical conditions.

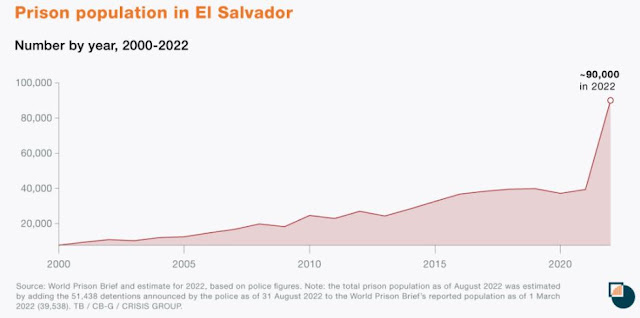

One thing abundantly clear is that El Salvador's prisons are now horrifically overcrowded. At the beginning of 2022, El Salvador's prisons held around 39,000 prisoners in a system with an official capacity of 27,000 according to World Prison Brief, citing Salvadoran government statistics. Thus the system was already over capacity, before adding 54,000 additional inmates in the past six months. In a system designed for 27,000, Salvadoran authorities are cramming in 93,000 persons, the vast majority of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime.

Stories like this one continue to appear – José Serafín Fuentes Guerraa was a 38 year old agricultural worker whose family did not learn of his death until a funeral home contacted them about receipt of a sealed coffin with his body. He had been seized by security forces four months earlier. His is one of 80 deaths recorded in the prisons since the beginning of the State of Exception. While it is not possible to say that all of them were arrested as part of the massive gang sweeps or that all died of abuse or torture, there is credible evidence that dozens did.

Salvadoran legal expert Wilson Sandoval was quoted in EDH lamenting the ” illegal arrests and deaths in penal centers of detainees who never knew the reason for their detention or saw a judge.”

Source: International Crisis Group

The Salvadoran courts have done little to respond to the widespread allegations of arbitrary arrests and detentions. With more than 1300 petitions for habeas corpus seeking to liberate those unjustly detained presented to the courts through early September, one set of data shows 99.65% of the cases have not been acted upon.

Meanwhile, Cristosal is warning about changes in criminal laws adopted by the Legislative Assembly and in proposal stage, which would make many of the measures of the State of Exception permanent.

The permanent exception regime is complemented by a political decision already taken previously by the groups in power which control the Presidential Palace to violate human rights and to saturate citizens with the idea that violating human rights is necessary or justified in the name of security,

Celia Medrano, journalist and human rights advocate.

The International Crisis Group (ICG) issued a report today titled A Remedy for El Salvador’s Prison Fever which all should read. Following an extensively documented discussion of events leading up to the State of Exception and over the past six months, the report goes on to tackle the important question of “What now?”

The ICG report notes that the current reduction in violence, with gang members arrested, or on the run or in hiding, may not last:

The campaign to arrest anyone who has, has had or may have had a link with gangs could force former members back into crime if they see no hope of anything else. Mass arrests of former gang members who have converted to Christianity in order to quit gang life are troubling. Dire overcrowding, combined with the government’s refusal to take responsibility for what has gone wrong – from custodial deaths to wrongful arrests – could fuel tensions in jails, leading to mutinies and escapes.

The need exists, therefore, to develop a plan allowing for reform and reinsertion of those tied to gangs, and not simply an attempt to warehouse them all in a mega-prison:

El Salvador needs a more humane and sustainable approach to solving its gang problem. A crucial plank of such a policy would be the creation of a clear pathway out of gang life for jailed and free members. Even as they seek to profit politically from fighting crime, Bukele and his senior officials should be mindful of the innate dangers of a huge prison population, which must be fed and housed, and begin looking for ways to release jailed suspects and convicts subject to their monitored participation in rehabilitation programs. Various bills to create a national rehabilitation scheme have been tabled in the country’s Legislative Assembly over recent years, but none has prospered; these should be revived. A rehabilitation and reintegration initiative should include measures that promote employment for former gang members, with support from churches and civil society.

The massive arrests of the past six months mean that El Salvador now incarcerates 2% of is adult population in hellish conditions, more than any other country on the planet. We have yet to see a long term plan to restore any portion of this population to society.

The State of Exception is the "new normal" in El Salvador, with the population seeming to have little concern with the evaporation of due process protections and human rights norms.

Comments